Common sense is only “common” to people who share the same underlying assumptions.

You have heard both sides of this argument. One side says that if you cut taxes, it gives industry more money to spend. More cash leads businesses to hire workers and create more products. The economy expands, and everyone does better in the end. It’s just common sense.

The other side argues that cutting taxes means the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. That side sees taxes as a way of making those who benefit most from society pay for those benefits and put more money in the average worker’s hands. Those workers then go out and spend money to buy the things they need. Increased spending drives demand for products, which leads industry to thrive: adding jobs and boosting profit. It’s common sense.

They can’t both be right. So which is it, more taxes or fewer taxes that makes the economy thrive. Economists have studied this question for decades and have reached a consensus. Are you ready? The best minds have concluded that it’s complicated, and there is no clear one or the other answer.

If there is no clear answer, how can people on both sides of the issues see it as simple common sense?

What is Common Sense?

People like to thinks that they come to their decisions based on rational thought and evaluation of the evidence. But the people who do that are the economists who studied the data and arrived at the conclusion, “it’s complicated.”

What the rest of us do is work from a set of assumptions. We have specific ideas about how the world works—many of those beliefs we accept without questioning them. We assume that is the way things are.

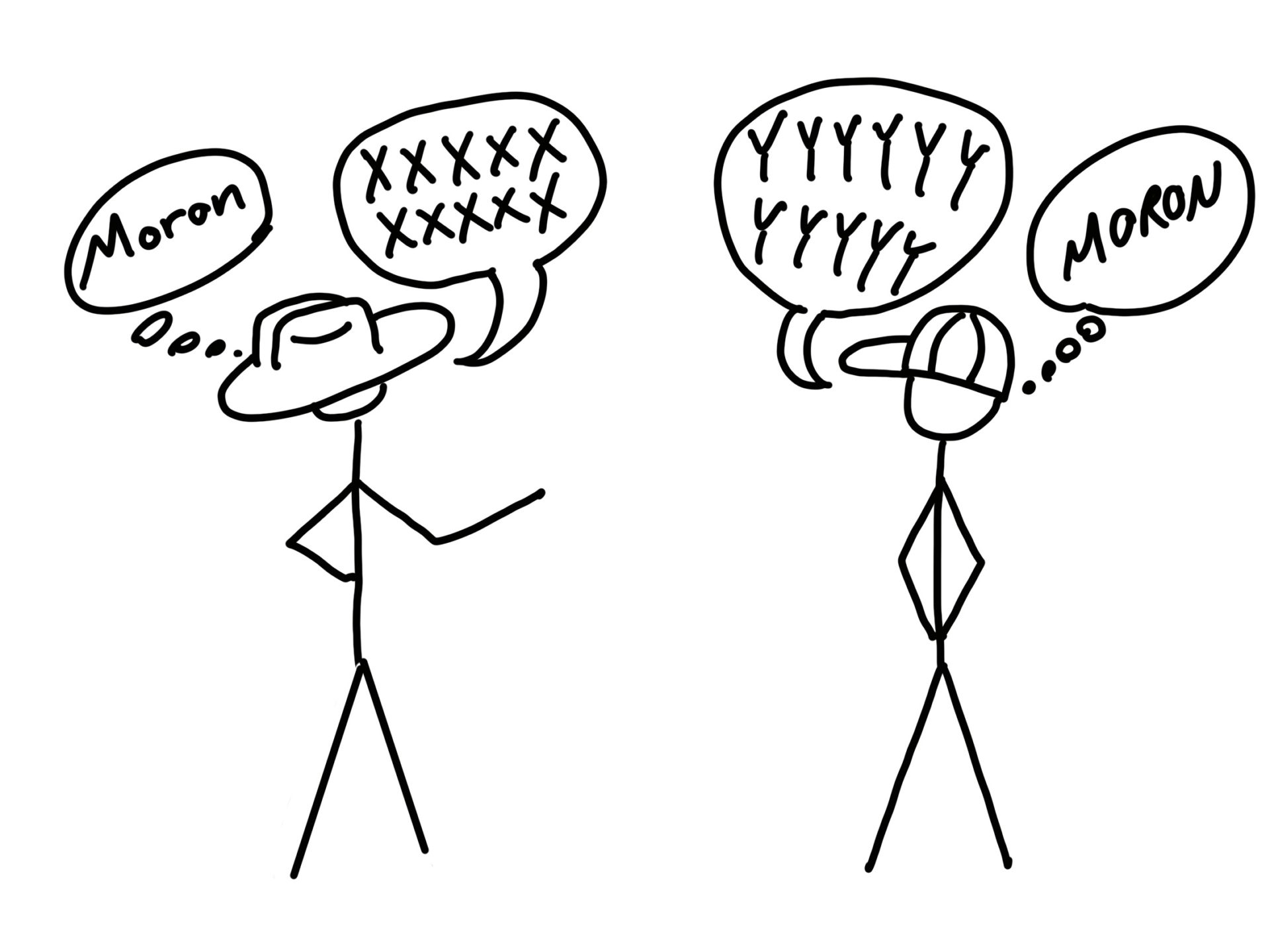

When other people share our beliefs, they naturally arrive at the same conclusions. We think those people have good common sense. But when people start from a different set of assumptions, they tend to arrive at a different conclusion. Since we don’t share their premises, we can’t understand how they arrived at their opinions, so we decide that they must be morons.

Common sense is only common if we share the same underlying assumptions.

We like to think we categorize people into those with good common sense and morons based on how those people think. But the reality is, we are judging them based on their underlying assumptions and how closely those assumptions align with our own. We accept an idea as common sense if it reflects our worldview, which means it shares our fundamental beliefs. In the end, common sense is more about judging than objective reasoning.

It’s your assumptions that get you in trouble.

The crux of the problem is our assumptions. Where do they come from? Are they true? Why do other people have different assumptions from ours?

Common sense comes from our experience, which is limited.

When we rely on our common sense, we rely on our own experience; however, our experience is limited. I recently had someone try to explain a complex economic policy to me by pointing to his brother-in-law’s experience running a local business. While I will accept that this family member may be knowledgeable about running his local business, I had to question if that experience extrapolated to complex economic theories of banking and derivatives trading. If the bother-in-laws business was running a hedge fund, I might have given the brother-in-law’s ideas more weight. But it turns out the guy runs a hot-dog stand.

There is so much to know about any issue that there is no way our personal experience can make us experts in all fields. I am an expert in surgery. I have been practicing it for more than two decades, and I ought to be good at it by now. But I recognize my expertise in one field of medicine does not make me an expert in all medical fields. Recognizing my experience’s limitations means I turn to people who are specialized in other fields when problems meander out of my specific area.

What is common knowledge to one person may not be to another.

A dietician friend once told me a story from early in her career that illustrates this point. She was counseling a patient on a low sodium diet. The nutritional expert went over a list of foods to avoid, appropriate substitutes, and the importance of looking at food labels. One week later, the dietician met back with the same patient. Over the week, the patient read the nutrition labels on foods and had come to a startling conclusion.

“Do you what is full of sodium?” the patient asked.

“What?” inquired the dietician.

“Salt.”

In going over all the information about a low sodium diet, it had never occurred to the well-educated nutritionist that the patient did not already know that sodium is salt.

It can be easy to overlook what we know that others may not. Even more damaging, people often have no idea what they do not know. You are no exception to this rule.

Common sense is more about feeling than thinking.

Ever have the occasion where someone said something that you just knew was wrong. At a gut level, you just reacted to it without thinking. But despite that conviction, you could not articulate in words why it was wrong. That is because our assumptions are often so deep-set that we don’t even think about them. They act more at the level of feeling. Some ideas feel wrong. We instinctively know they cannot be right even when we can’t articulate why we think that.

When assumptions get that deep-set, we often don’t question them because it feels wrong. The result is that we don’t want to examine those sacred convictions and become offended if anyone dares to disagree with them. Rational discussion breaks down and gives way to righteous indignation. Yet, these fundamental and unquestioned beliefs may be some of the most important to take a step back from and think about rationally.

How do we question our assumptions?

The hardest part of evaluating your assumptions is recognizing that you have them. As I mentioned earlier, those assumptions can be so deep that we don’t even realize we have them. One method for coping with this blindspot is to notice when an issue elicits an intense reaction from you. Then take time to reflect on that issue. Ask yourself what assumption underlies that response. Now go deep and ask yourself why you believe what you believe.

Ask “Why?”

The trick here is not to stop asking “why?” too soon. I have found that asking myself, “why?” five times, gets me to a deeper understanding of my belief. For example, I may react negatively to the idea of building a colony on the moon (for the record, I think moonbases are cool).

Why did I respond that way to the idea of a moon colony?

I don’t see the point of spending all that money.

Why don’t I want to spend that money?

Because I think it will cost more than we will get back in benefit?

Why do I think that?

Because we could use that money, and the science, to solve problems here on earth?

Why problems on earth?

We are not looking after the earth’s natural environment. Why should we be working on an artificial one for the moon?

Why does that bother me?

Because I want my children to have a healthy place to live, and it won’t be on the moon.

Now I have a better understanding of what my real priority is. I can use that insight to stop railing against a moon colony and start supporting sustainable technology on earth.

Question the limits of your own experience.

By the nature of being simple humans in a complex world, it is unlikely that we have enough knowledge and experience to understand all the issues that face us. Ask yourself, “Does my experience really extrapolate into this area?” If the answer is no, then ask, “How can I learn more?”

There seems to be a war against expertise in America today, but educated experts are your best source of information and understanding. Look for those in the mainstream who are respected and referenced by their peers. Avoid the talking heads on TV and radio who pass off opinion as fact. Look for people who speak to the one field where they are an expert and were other knowledgeable people support them. When it comes to expertise, it is best to avoid the people on the fringe.

Question the limits of other people’s experience.

When listening to people express an idea, remember that their experience and knowledge limits them. Ask yourself, “How much experience and knowledge does this person have in this area?” If it is brother-in-law talking about how to run a hot-dog stand, then you will want to listen. But if the hot-dog vendor is discussing derivative trading, you may want to question his expertise on that topic before you invest your child’s college savings.

Conclusion

In the end, it is a line from that father of homespun American wisdom, Mark Twain, that comes to mind,

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

— Mark Twain

Recognize that most of what you accept as common sense is just a set of unquestioned assumptions. Then question those assumptions. Look to the counsel of those who are more knowledgeable about the topic. Seek out contrary opinions and uncover the sources of those opinions. Ask Why? Why? Why? Why? Why?

Did you find this interesting or helpful. If so, feel free to share it with anyone you think may benefit from it. And check out the ChuckBPhilosophy.com blog for more.