We often don’t know what we are doing, but we can’t stop.

A famous heart surgeon was waiting for his car at the dealer when a mechanic recognized him.

The cheeky mechanic waved the surgeon over and pointed to the engine. He showed the famous surgeon how the repairman replaced worn hoses and leaky valves. The mechanic pointed to his work, “Look, you and I do the same work. So why do you get paid the big bucks to do the same job?”

The surgeon inspected the mechanic’s efforts, then turned to the repairman and whispered, “Try doing it while the car is running.”

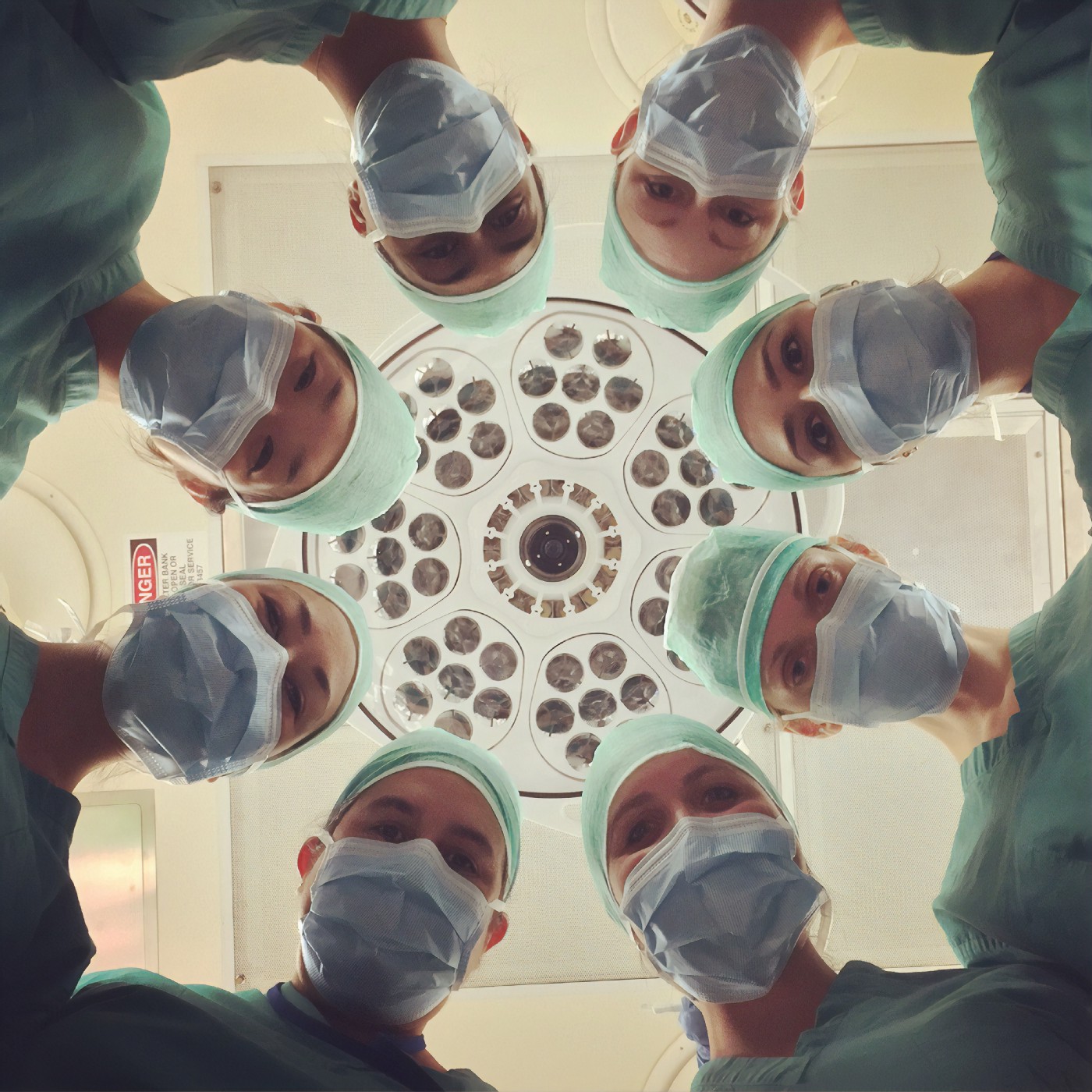

I don’t know how accurate this story is, but the underlying truth remains, working in healthcare means working on a car while it’s running. We don’t have the luxury of turning off our problems and putting them in the corner until a perfect solution is devised or a replacement part arrives. We have to work in a living system while it is running and with only the things available to us at the time.

The Coronavirus pandemic demonstrated this truth of medicine to people who had not seen it before. Not that it is a new problem, but that people outside of doctors and some patients exposed to the realities of modern medicine.

When the patients first started arriving in hospitals with this novel infection, we did not know how to treat it. We had good practices for treating similar illnesses, but no one had ever treated this virus before. We were in uncharted territory.

It would have been nice if we had the luxury of a few years to study the virus and its effects and better target our response. We would have seen fewer missteps. But while patients in respiratory distress piled up in the ICU, we did not have the luxury of time. We needed to treat these people now.

You could say mistakes were made, but that’s not really fair. Calling something a mistake means that we knew the correct answer. But medicine is not high-school algebra. While two plus two always equals four in math class, the calculus of biology is much more complex. What works on the cellular level does not always transfer into a living organism’s much more complex chemistry and biology. The interaction of organs, hormones, the immune system, and medical therapy is a maze with many dead ends.

So medicine did its best, but it did not get the response right. We tried medications and treatments that failed, not because they were a bad idea, but because the body has its own logic. A logic that sometimes defies our ability to predict. We tried the things that made sense based on what we knew and then waited to see what the results were. And some of those results were . . . disappointing.

Medications that showed promise in a petri dish showed no effect and possibly caused harm when given to infected patients. Old rules for dealing with patients in respiratory distress, like the early use of ventilators, proved to be suboptimal in the care of patients with COVID. So doctors noted these results and adjusted treatment as they went.

Our only choice was to learn how best to treat patients as we went along. Medicine did not have the luxury of waiting until the laboratory had rigorously tested the treatment options because patients didn’t have the luxury of waiting. It would have been unethical not to do our best to care for people as best we knew how even when we knew our knowledge was lacking.

People have expressed concern about how quickly pharmaceutical companies developed a new vaccine. I will admit, it is impressive how quickly we had several options. But saying it happened that fast is an oversimplification. The underlying research in vaccines has been ongoing for decades. That long history of research performed behind the scenes made these vaccines possible. They aren’t really new vaccines; they are a new extension of research that has been going on for decades in preparation for a scenario like COVID-19.

Were these vaccines rushed into use? Many feel they were not adequately tested, and if they mean we don’t have years of data on the vaccine’s long-term effect, then those critics are correct. Medicine had to run studies to establish that the vaccine was effective and safe in the limited time they had. The only way to find out the ten-year treatment results is to wait ten years and see what happens, but we didn’t have ten years to wait. People were dying, and we needed a good way to stop that now, not a perfect way to do it in ten years.

Everyone would like to know the twenty-year effects of a treatment before they start it. But I can tell you from experience that when the current therapy has failed, that experimental treatment — despite all its unknown — starts to look pretty enticing. The patient dying from cancer today can’t wait twenty years to determine the long-term effects of a new treatment. They need to make a decision today with the imperfect available data and hope for the best.

The problem is we have to treat people and problems as they appear. That often means initiating treatment before we know all the facts. The body and the healthcare system are dynamic. Doctors and nurses work on the car while it’s running and without access to spare parts.

I spent time on a farm when I was growing up. I learned that when it is harvest time and an essential piece of equipment breaks, you can’t wait a week for a new part to arrive. When the new part arrives, it will be too late, and the crop will be lost. So if you can’t beg, borrow, or steal help from a neighbor, you have to find a way to limp through with a homemade baling wire and duct tape solution. When you find yourself in this situation, you get creative and invent a solution. The one thing you are not allowed to do is give up.

Healthcare providers did not give up. Despite having no effective medications, tested treatment plans, vaccines, or even the personal protective equipment to keep themselves safe, healthcare workers soldiered on. They kept showing up, working on the problem, and learning as they went along. And yes, they created more than a few baling wire and duct tape solutions to try and help their patients. The first efforts were not as effective as we would have liked. There were missteps, blind alleys, and some advice that seemed wise but proved to be ineffective in the long run. That is what happens when you work on a novel problem in uncharted territory.

When you think about it, all advances in medicine occur in uncharted territory. We constantly create new treatments for problems, new medications, surgeries, technologies, and implantable devices. So the unknown territory is not new to medicine. The medical system has more tools and knowledge than ever before, but we don’t have perfect tools or expertise, and we never will.

The COVID pandemic showed us both the power of modern medical science and the ingenuity and resilience of healthcare providers. The pandemic also demonstrated the limitations of what we can know and do. The only way to find out the long-term results of a medical treatment or vaccine is to wait decades. But while we wait, people die. We find that unethical, so we do the best we can with the knowledge and tools we have at our disposal while working to sharpen those tools and build a better understanding.

Doctors don’t have the luxury of turning off the ignition and working on a problem while it sits quietly and waits for us. We have to try and repair the car while it is running, but we must all accept that we will never be perfect.